Chainsaw Man ages like fine wine. It feels like not too long ago that I read Chainsaw Man as it was serializing, and while I enjoyed it, I wasn’t blown away. I’m aware of what that says about me; perhaps I was simply inexperienced in analyzing manga, and what makes one truly great. It seemed like a solid story with phenomenal art at the time, but nothing more.

Since then, I’ve had a lot of time to think about both Chainsaw Man and the review I wrote. In the end, I was wrong. Chainsaw Man isn’t just a good manga, it’s the newest pinnacle in shonen’s decades long competition to perpetually one-up itself. Chainsaw Man is simultaneously an approachable, accessible story like the best of Shonen Jump, while being deceptively complex and rewarding to reread and pick apart.

Tatsuki Fujimoto does this by playing to the familiar formula that’s crafted SJ’s classics and new hits, while frequently breaking out to carve a strange new path for itself. It’s often cryptic, psychedelic, and downright bizarre, but it never abandons the plain appeal of the genre.

The first way that Chainsaw Man plays the same song in a different tune is in its protagonist. Denji is a teenage boy forced into harsh circumstances outside of his control, a lot like other contemporary battle protagonists. He’s sixteen and drowning in debt to the yakuza, thanks to his deceased father, so he makes a living selling his organs and killing devils with the help of his friend Pochita, the Chainsaw Devil.

After the yakuza turn on him, and Denji’s mortally wounded by a devil, Pochita makes a contract with the boy. He’s listened to Denji wistfully daydream about the kind of life they’ll have one day, and in return for Pochita giving Denji his heart, all he has to do is go out there and live the life they talked about.

The contract grants Denji new powers as a human/devil hybrid, a rip cord in his chest he needs to pull to grow chainsaws from his arms and head. Almost immediately after surviving this encounter, though, Denji’s now in the sights of the Public Safety devil hunters, but it could be worse. His boss, Makima, is a cute girl who Denji wants to step on him, and he gets the three square meals and a warm bed he and Pochita chased after. Now he’s just got to go kill some devils to earn it.

Chainsaw Man sets up its story similarly to many other shonen manga; in my review, I called it the new Devilman specifically for those similarities. It bears a strong resemblance to its Shonen Jump peer Jujutsu Kaisen, among others. It also establishes the kind of story where Denji can fight many different kinds of foes, thanks to devils’ broad nature.

Devils are born from the fears of mankind. The more people are scared of a concept, weapon, or object, the more dangerous the devil. The obvious answers occupy the middle of the demonic power range, like the Katana Devil, the Zombie Devil, and so on. The upper echelons, however, are occupied by abstract fears, the primal devils, like Control, Hell, and Darkness.

This gives Chainsaw Man a straightforward appeal from having an intuitive mythos and power system, as well as a relatable protagonist. Maybe he’s too relatable.

Denji is a simple boy, exceedingly so. Jump heroes are defined by their tenacity and single-minded attitude towards their ambitions. Deku wants to be a hero, Asta wants to be the wizard king. Their stories are conjured up around their goals, and the obstacles they face, giving their heroes a reason to move forward. Denji, though? He wants to touch a boob.

Denji’s never had the kind of life where he could wish for normal. He’s content when he can eat good food and not worry about where the next meal comes from. But, as Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs makes clear, once the basic needs are met, Denji has to start thinking bigger. And in return for slaying Public Safety’s most dangerous target, the Gun Devil, Makima writes Denji a blank check for anything he might ask of her.

It’s a brilliant subversion of the archetypal shonen hero. Denji isn’t possessed by incredible grit or a profound magnanimity, nor even an altruistic attitudes towards other people. He’s a teenager, with all the selfish, unrefined decision-making that entails.

And these flaws give Denji the exture that more main characters need. Don’t get me wrong, I love lawful good types like Deku and Tanjiro, but an entire genre can’t subsist off of the same protagonist. Many shonen manga leads are made relatable by suffering crappy circumstances; Asta doesn’t have magic, Shinra’s blamed for his family’s deaths. Denji’s circumstances are tragic, but not relatable. He’s made sympathetic because Fujimoto wrote a character who you could easily catch reading Shonen Jump, assuming he knows how to read.

But Fujimoto didn’t call it a day after writing a banger of a lead; his attention is spread efficiently across the supporting cast. You wouldn’t think an unhygienic, egotistical gremlin like Power could be a competently written, fleshed-out character, but he makes it look easy. Watching this fiend grow fond of Denji and their handler Aki is so endearingly written, while not canceling out her personality defects.

I’ve written about this before, but character development does not equate to erasing the person they were before. Writers, usually not good ones, will be uncertain how to write a character after they finish an arc, so they’ll just cross out their personality. Early on in Darling in the Franxx, Zero Two is mischievous, prone to stirring the pot and provoking conflict for conflict’s sake. By the last third of the series, to demonstrate she’s experienced growth, the writer neutered her of the antagonistic side that made her interesting in the first place.

Character arcs are intended to give the character a better view of the world, make them well-rounded as a person, or correct a fundamental mistake or belief. However, that doesn’t disregard their basic flaws, quirks, and traits just because they made some friends or started a relationship.

Power is an objectively awful person, willing to kill Denji first for her cat, then in service of her goal to win a Nobel Prize and become prime minister. She wants to do this, by the way, so she can make everyone’s lives worse by implementing a 100% sales tax. Gosh, I love her. Even so, by the end of her arc, she’s willing to put her life on the line for Denji.

And while I mentioned Aki in passing, I don’t know if there’s enough space in a book to write about this guy. Like many Public Safety devil hunters, he lost his family to the Gun Devil and dedicated his life to revenge. He made a contract with the Curse Devil to obtain a powerful sword that shaves years off his life whenever its drawn.

At first, he’s the same no-nonsense, levelheaded deuteragonist we’re used to in these kinds of stories. You could call him an equivalent to Todoroki or Fushiguro, if you wanted to compare. However, a significant portion of the story follows his struggles alone, losing his friends to devils, and not just coming to terms with his mortality, but everything that will be left unfinished when he dies.

He doesn’t care about most of that, at least at first. He smokes because he won’t live long enough to see the toll it takes, and he’s reckless in battle because he’s the one in control of when his hourglass runs out. Even so, something about watching Denji and Power, these overgrown misbehaving children, cracks the shell he’s retreated behind. It gets to the point where he requests that the three of them be excluded from the expedition to hunt the Gun Devil. With as little time he has left, he’s unwilling to pursue revenge if he has to watch more friends die.

And there’s so much to talk about for both these characters, and the entire cast. Even the entire section and a half on Denji didn’t cover him, but I could spend all day dissecting side characters. Makima deserves the endless library of the Cosmos Devil, but I don’t want to spoil anything more for you than I already have, if you haven’t read Chainsaw Man.

And I said read Chainsaw Man, not watch. Don’ t get me wrong, I’m sure director Ryu Nakayama and the animators at MAPPA have a handle on things, especially when you’re handed a brilliant title like this. It’s just that Tatsuki Fujimoto is a master of creating manga, and it’s really a shame if you don’t get to experience this story in the way it was intended to be viewed.

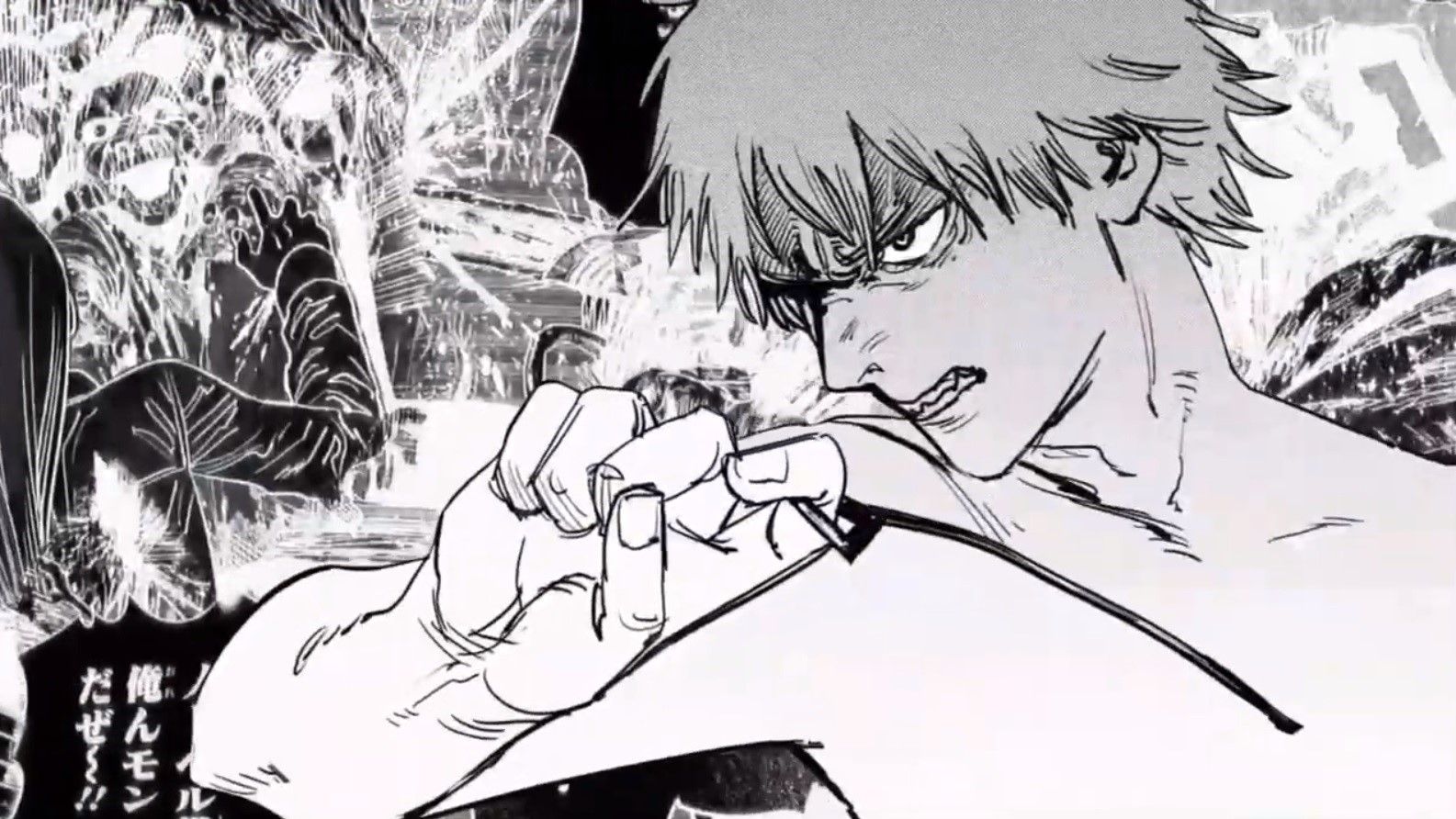

In my review, I did praise the airt, but I didn’t touch on just how good it was. It’s not as polished as many Jump heavy hitters, but its character designs are sharp across the board. Most of them wear the same black suit office attire that serves as Public Safety’s uniform, and yet their faces and personalities stand out clearly. They’re all so expressive; if not, then all that good character development I talked about would be for nothing.

And the fights are head-and-shoulders above the rest. Every single splash page illustration is a Renaissance painting of gore. The designs of devils can be eldritch, enigmatic, or downright uncanny, but they’re all lavishly produced considering how little screentime many of them get. Personal favorites would be the Fox and Future Devils, but some of these creatures receive brilliant designs, show up for one panel, get torn to shreds, and are never seen again.

And Fujimoto plays with panel layout and perspective like a master of the craft. I don’t think that I can do this justice in words because it was meant to be a visual experience. If you’re debating between reading Chainsaw Man and waiting for it to be animated, you’re doing yourself a tremendous favor by reading it. I assure you that it will be a delight to watch it come to life, but you should have an idea of what it looked like before then.

This was a little longer than most of my essays, partially because uploading weekly means I can spend more time on them, and partially because Chainsaw Man deserves as much time as I can afford to spend on it. Seriously, though, this was a difficult one to write; there’s at least three discarded rough drafts, and this barely survived the editing process. So, uh, like, comment, and follow the Otaku Exhibition on WordPress and Twitter @ExhibitionOtaku, yeah?

Aside from shamelessly plugging myself, I’d also like to hear what your journey was with Chainsaw Man, whether you read it before watching it, or are waiting for MAPPA to do it justice. My experience has been unexpectedly long and full of twists, and I’m sure I’m not alone in that.

And here’s the part where I tell you that even if you’ve already read Chainsaw Man, do it again. It’s a brisk 97 chapters, it’s available on the Shonen Jump app for $2/month, and you can crank it out really easily. Seriously, this story gets better every time I go through it, and the pacing is buttery smooth. The whole deal flies by.

So with that, I’ll take up the mantle of praising Chainsaw Man only once more when the anime begins airing, assuming Nakayama and MAPPA make it into the masterpiece it deserves to be, and already is. If not, I’ll have a bone to pick, and all my dozens of followers will hear about it. Until next time, thanks for reading.

3 responses to “Chainsaw Man is the Perfect Shonen”

Most overrated new gen manga it’s literally nowhere near perfect 5/10

LikeLike

Could you elaborate? Calling something overrated doesn’t really say anything about the quality other than it’s popular, so if you have more specific critiques of Chainsaw Man, I’d love to hear them.

LikeLike

[…] briefly touched on it in my essay on Chainsaw Man last year, which you can read here, but there’s a good reason for Chainsaw Man’s runaway success. I mean, it’s just […]

LikeLike